The Korean Wave – or Hallyu – was only just beginning to gain traction globally. That was the time of the ‘second generation’ K-pop stars such as Big Bang and 2NE1 (pictured below) whose reach was extending beyond the country fandom.

Outside of the pop world, there were a few K-movies and K-drama titles that became hits in neighboring Asian countries. The dish bibimbab was being served by airlines, kimchi was being promoted as the next health food, petitions were submitted to the UNESCO World Heritage list.

In search of lost culture

That said, when I went to attend a traditional wedding in the deep countryside, no one knew what to do. The ceremony master was reading the script out loud, and people were trying to perform the rites but were clearly confused. Insadong, a popular Seoul neighborhood where both natives and visitors gather to experience traditional culture, had its main street overflowing with mass-produced souvenirs, while the authentic craftsmanship you can see nowadays was mostly hidden.

Fast forward a few years, and as a Painting major at Ewha Woman’s University in Seoul, more and more intrigued by the local art scene, I began asking my classmates for book recommendations on Korean art history. I was mostly met with silence; and a visit to the largest local bookstore proved that there really was very little to see – even in Korean language. A few general books on Asian art history, some books on traditional Eastern painting – the staff assisting me weren’t quite sure what to show me. What about the modern artists, surely there must be something?

Then, finally, something changed and in 2013 the book Contemporary Korean Art: Tansaekhwa and the Urgency of Method written by Joan Kee was published – still one of the most important English-speaking publications on Korean art. Interestingly enough, the book was supported by a grant funded by the Government of the Republic of Korea, a clear sign of the effort that went into this type of initiative behind the scenes.

In 2015, at the Venice Biennale, Dansaekwha (also known as Tansaekhwa) or Korean monochrome painting became the talk of the town (see photo) and soon afterwards other more sophisticated expressions of Korean culture began gaining recognition. There were large retrospective exhibitions at private galleries and the National Museum of Modern Art; Korean artists started signing on with well-established French art galleries and their artwork was purchased by the most prominent global art collections.

In 2020, the renowned art publisher Phaidon released the book Korean Art from 1953: Collision, Innovation, Interaction which it introduced as “the first survey to fully explore the rich and complex history of contemporary Korean art”. Now, bookstores are filled with both domestic and international explorations of Korean art in particular, but also other – even very niche – aspects of the local culture. There are titles covering highly specific traditional crafts e.g., Maedeup, Korean knots, or fascinating subcultures such as Haenyeo, the female divers from Jeju Island.

I recently read an article in the British magazine System on “the meteoric rise of K-pop in luxury fashion, as told by those who helped instigate it”. It talks about the first official K-idol group, Seo Taiji and Boys – the first generation of K-pop, whose debut in 1992 became the foundation for the phenomenon we are experiencing now. It also talks about the 1988 Seoul Olympics, Korea’s first big entrance on the international scene, and how in reaction to the 1997 Asian financial crisis the Korean government decided to bolster the economy by investing heavily in cultural exports.

While mostly focusing on pop culture, this piece echoes what I have witnessed and experienced over the past 15+ years of my life in Korea: local cultural shifts, global events, thoughtful government policies, lots of hard work and amazing talent. Three decades since the first seeds were planted, the latest world craze, K-culture, is in full bloom.

The luxury connection

Existing between two superpowers, Korea has a difficult history – one I can appreciate and definitely understand as a Polish person. After centuries of living in the shadow of other countries, Koreans appreciate being appreciated. The more attention which is given to Korean culture, the more amazing aspects it brings (back) to life, forming a virtuous circle.

Perhaps this is one of the reasons why the relationship between luxury and Korean art and culture (modern and traditional) fascinates me so greatly. Luxury companies have the power to amplify voices globally and, when I first noticed collaborations between brands such Dior or Louis Vuitton and Korean painters, I felt emotional, proud, and happy for Koreans.

I also saw this as the answer to a years-long personal conundrum. How could I combine my experience in business development within the Korean digital commerce and consumer goods sectors, my in-depth knowledge of Korean culture – which I have gained throughout almost two decades of study, but also by speaking the language and living my life as part of Korean society – and my deep love of art?

With these new developments, finally, everything made sense.

More importantly, my enthusiasm is backed by numbers. The Korean art market was the 7th largest globally in 2022, alongside Japan and Spain, worth USD 782m – figures representing a 32.2% year-on-year growth. While it is currently experiencing the same issues as all art markets globally, based on its steady growth over the years, I believe it is here to stay. Kiaf, the Korea International Art Fair, and Frieze Seoul continue attracting more and more attention with each passing year of their partnership. The Seoul Art Week they are part of is now also the culmination point for art-related initiatives carried out by luxury brands.

YSL, Chanel, Dior, Cartier… the biggest names come out to play

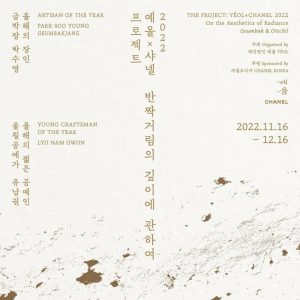

In 2022, the first year of Frieze Seoul, Saint Laurent (see main image) staged an exhibition of the visual artist Lee Bae. The same year, Chanel started a 5-year partnership with the Yeol Korean Heritage Preservation Society, through which the maison has been supporting the Artisan of the Year and Young Craftsman of the Year projects (see picture below).

Furthermore, Luis Vuitton invited the now late artist Park Seo Bo to design a bag as part of its ArtyCapucines collection and – a lesser known fact – four years earlier, in 2018, it also invited Korean stylist Seo Young-hee to design a special edition trunk influenced by traditional marriage culture.

In 2023, Dior held the Lady Dior Celebration exhibition which showcased 42 works of 24 Korean artists with which the brand has collaborated over the years, starting as far back as 2012. Meanwhile, in June this year, Cartier held a large exhibition at the Seoul Dongdaemun Design Plaza. There it showcased a traditional fabric restoration project it has been funding since 2015 in partnership with Onjium, a research institute established in 2013 in affiliation with Arumjigi Culture Keepers. The pioneer that it is, in 2007 in Paris, Fondation Cartier hosted an exhibition of the now world-renowned Lee Bul.

The above are just some of examples of this incredible luxury and cultural cross-pollination. But there are plenty more – for example, a young Korean artisan, Dahye Jeong, won the 2022 Loewe Craft Prize. Five of her compatriots were among the 30 artists shortlisted for this year’s edition. Hermès regularly introduces Korean artists through the Fondation d’entreprise Hermès – in April this year it was Tak Young-jun’s exhibition at Atelier Hermès in Seoul. Last year Bottega Veneta highlighted the Korean kite artisan Rhee Ki-tai through its Bottega for Bottegas program. In 2020, the young artist Seonglib created designs for Prada’s Re-nylon popup art collaboration.

There are no doubt plenty more examples I’ve missed out, since almost every day I discover more initiatives through my research on the topic of luxury ‘artification’ in the Korean context.

All of this to say – yes, this ‘K-phenomenon’ is undoubtedly ramping up; but in fact Korean culture has been gaining in significance year by year for more than 30 years now. And it is recognized not only by global luxury brands but also the Korean people themselves.

The government, too, is committed to further nurturing it. In 2022, the South Korean president Yoon Suk-yeol announced a USD 3.7 billion investment in arts to make the country even more “culturally attractive”. This is no one-hit-wonder like in pop music, but the result of steady progress and relentlessness. And not unlike those storied luxury brands I mentioned earlier, if this cultural awakening continues to be steered wisely, these wondrous efforts can become the foundation for centuries of glory to come.

About the author

Dominika Kustosz-Lee is a Korean market expert, who specializes in designing, managing, and executing technology-infused art and culture projects that enrich the connection between global luxury brands and their Korean customer base. With a deep understanding of the latest trends and developments in e-commerce, digital marketing, and consumer goods, she leverages her background in fine art to conduct research on the ‘artification’ of luxury in the Korean context.

Dominika has collaborated with executives, VPs, and C-level stakeholders to develop localized client journeys and engagement strategies. By expressing a strong connection to contemporary culture and a commitment to the local art community, she helps global luxury brands forge meaningful relationships with their Korean customers.

A resident of Korea for more than 15 years, and a Korean citizen since 2020, Dominika is fluent in the language and culture, allowing her to navigate the nuances of the market with a high level of cultural sensitivity. With a strongly developed sense of responsibility, ownership, and a collaborative spirit, Dominika is passionate about delivering exceptional customer success and experience.

Connect with her on LinkedIn

Photo credits

Main image: Chung Sung-Jun/Staff/Getty

Seoul skyline: Siraphol/Getty