Rashid Khan is not a name known to many Americans. But any cricket fan — which includes the heads of Microsoft and Google — knows exactly who he is: a famous Afghan cricket bowler with a devastating version of a pitch known worldwide as a googly. It’s a pitch that every batter thinks they know how to hit. Yet time and again it fools them, and they are out. I wonder if Khan’s bowling comes to Sundar Pichai’s mind as Google grapples with the sudden but all-too-predictable shift to the new “AI” era. Google’s search engine revolutionized the internet. But in the face of Microsoft-backed OpenAI, Perplexity, and a slew of other new AI companies, Google search is starting to look old, tired, and less and less useful.

By now you probably know that a US federal judge declared Google a monopolist this week. Google has been paying Apple billions of dollars to remain the default search engine on iPhones and other Apple devices, a practice a federal judge has now ruled against. This ruling will resonate, leading to speculation about its implications for the rest of Big Tech and potential penalties for Google. Meanwhile, lawmakers and regulators will congratulate themselves on bringing yet another Big Tech company to heel.

And all of it will completely miss what’s really going on competitively in Silicon Valley right now. There seems to have been a five-alarm fire at the Googleplex for more than a year, with no one there able to extinguish it. However, this has nothing to do with the government’s antitrust lawsuit.

Google, the monopolist, has never faced more competition. Like Microsoft 25 years ago and IBM 45 years ago, Google is proving ill-equipped to respond to these competitive threats. Like Microsoft and IBM before it, Google is facing competition that comes in the form of a new behavior, which is very different from what has made it so successful. This new behavior attacks the core of Google’s money machine — the 10 blue links and the advertising dollars wrapped around them.

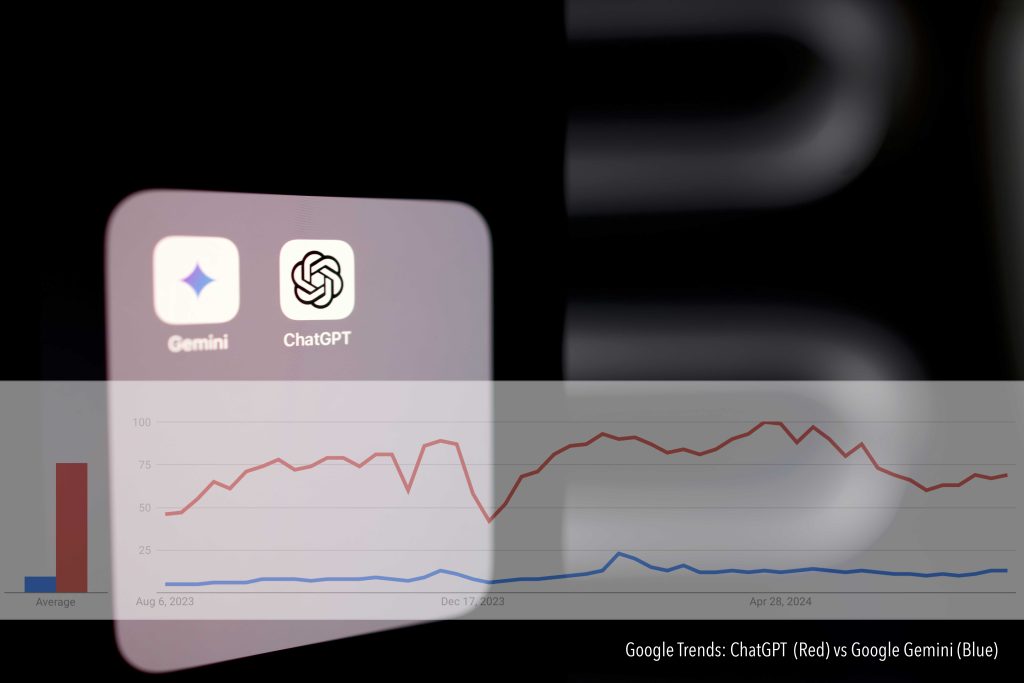

With ChatGPT, OpenAI has effectively created a next-generation search engine. Instead of a list of links and ads, it provides an answer, increasingly the correct ones. Everyone I know who used to “Google” things is now “ChatGPTing” them. You don’t need an MBA to know that’s not only bad for Google but existentially threatening. With Microsoft’s financial backing and global reach, OpenAI has the resources to enhance ChatGPT and make it ubiquitous. A recent deal with Apple won’t hurt either. What OpenAI started has been further propagated by rivals such as Anthropic, signaling a significant shift in the search engine landscape. We are witnessing Google being “Yahoo-d.” (See footnotes)

It’s been painful to watch. ChatGPT took the world by storm nearly 20 months ago, and Google still hasn’t delivered a competitive product. This situation is especially disappointing considering Google’s history. What ChatGPT has achieved is exactly what Google’s founders and former CEO Eric Schmidt envisioned more than 20 years ago—an answer machine. For years, Google featured an “I’m Feeling Lucky” button on its home page to honor that pursuit, to show that Google’s Search was so good that displaying the first search result was all most users needed.

None of these changes have affected Google’s bottom line yet, just as it took years for Microsoft’s sclerotic response to Google and Apple to show up on its income statement and stock price. But other signs of decay are evident. Google’s brainiacs invented much of the technology driving the entire artificial intelligence community. However, a lot of that talent has left the company, frustrated by its increasingly sluggish approach to innovation. Some have started to trickle back, but it might be too little, too late.

WHY THIS MATTERS

The new ruling from the judge is going to slow down what was already a slow-moving company. I saw legal troubles throw a spanner in the works for Microsoft — something I witnessed firsthand as a reporter. I learned about IBM’s troubles from my editors. There’s no denying that there will be ramifications for Google — the biggest will be an even slower pace of innovation at the company when it needs it most.

Why? Because we’re amid another long-term transition in how we interact with information, affecting how we use the internet. The last era, defined boldly by search, is almost over. The antitrust actions come long after the party has ended, as I’ve mentioned before.

The pressures on Google, exacerbated by mediocre leadership, will only hasten what the natural evolution of technology was quietly unleashing: The internet is on a trajectory of hyper-personalization.

Social media was a big step forward. Mobile personalized how we interact with information even further. Together, these turned Facebook into an advertising powerhouse. Google survived (and thrived) by building its own sources of personalized data: maps, emails, Chrome, and Android operating systems. The next obvious step is personalized answers, generated one query at a time. This should be Google’s sweet spot — it isn’t.

Why? You might have heard me say it before, but I’ll say it again: The company is trapped in a 10-blue-link prison. For almost a decade, I’ve argued that Google seems to be the most vulnerable of all big tech companies. Even though it has helped create technologies that have enabled people to think differently about data and machine learning, it remains a one-trick pony. Search dominates its revenue stream, with YouTube a distant second. The rest of the company’s endeavors — Google Cloud, Android, and projects like Waymo — aren’t big contributors to the bottom line. As a result, the company focuses all its energy on search.

Anecdotally, there is a widespread perception that Google’s user experience is declining, with search results showing one sponsored link after another. As one former Google employee said, “By being a de facto monopoly, there is no motivation to trim the number of ads that need to be shown.”

Newcomers like OpenAI, Anthropic, and Perplexity are creating what Google talked about when it started the company: an answer machine. The funny (or sad) thing is that Google possesses all the necessary tools for a counterattack: robust cloud infrastructure, chip expertise, and the technology to develop its own answer engine. It has captured user “intent” already in its algorithms.

NOT THE FIRST TIME

Fifteen years ago, it seemed Facebook might challenge Google in search the way OpenAI is challenging Google now. That didn’t happen. Instead, Facebook expanded the menu of options for users online. Even though Google’s social networking attempts fell flat, the company managed to survive by triangulating consumer data to offer better, highly targeted advertising that married intent and effectiveness. Google and YouTube kept hoovering up the display ad dollars moving online.

AI-based competitors pose a different, more existential threat to Google because they offer what most users have wanted all along: an answer machine, not a search engine. This is similar to what Google did to AltaVista and other internet portals 25 years ago, marking the first time Google has faced such a challenge.

They are portending what the internet needs today. The information online is becoming plentiful and disorganized. We need new ways of organizing it. Whether it’s Google, Facebook, or Twitter, the internet is messy and increasingly unusable due to the rapid influx of information. We are also staring at a future beyond the browser—a future of mixed reality, enabled by much faster networks and more powerful semiconductor engines. This new world will require a new layer of information interactions.

As I wrote on the blog earlier, a post-Web 1.0 world for me meant anywhere, anytime, on-demand computing, thanks to cloud and mobile as enabling technologies. These would redefine and create new behaviors. Social networking, a critical new behavior, has defined how we have interacted with data online for a decade and a half.

AI is a critical part of a new framework for organizing various trends. It will increasingly determine how we interact with data and thus shape our consumption of knowledge.

Generative AI not only answers our questions but also creates images, videos, and audio at line speed, assembling content as fast as data packets arrive. While cryptocurrency today might be associated with scammers, it has the potential to become a distributed authentication layer that separates information from disinformation. Are we there yet? Not really — but remember, we started with GeoCities and ended up with Instagram and Facebook.

OpenAI could be AltaVista or Google, or MySpace or Facebook — that isn’t important. What’s important is that we are at the start of a fundamental shift in how we interact with information. This will impact every player who relies on the classic idea of “web pages,” “page views” and the advertising economy that supports it.

With every shift in web technologies, we see changes in how, when, why, and how often we interact with information, leading to new behaviors and a new web order. Companies that don’t anticipate and adapt ahead of these shifts start to lose their prominence and eventually their place at the top.

In his 1997 book, “The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail,” the late Harvard Business School professor Clayton M. Christensen argued that established players struggle to adapt because they focus too much on their current business model and fear disrupting the status quo. Their priority is to goose the revenues through incremental improvements. For public companies, the pressure to grow revenues and show profits makes the established players focus on the near term, thus missing long-term challenges.

Google seems to be caught in that dilemma. In 2008, I called this being trapped in the “10-blue-link” jail. Almost everything the company does is dictated by the revenue it makes from sponsored ads at the beginning of each search. The last time I checked, that revenue totaled about $165 billion, just for the first six months of this year. It is hard to mess with that money machine.

“We were iterating to ship something, and maybe timelines changed, given the moment in the industry,” Google CEO Sundar Pichai told The Wall Street Journal. “It has been incredible to see user excitement around adoption of these technologies, and some of that is a pleasant surprise as well.” That’s prime corporate speak. Google’s attempts to deliver a competitive offering have not been competitive at all.

Google of today is no longer a product-centric company; instead, it is a collection of managers running the money machine. It hasn’t developed a single new hit product in over a decade. Android, Google Maps, Gmail, Google Docs, and YouTube were either acquired or developed in a different era. This is also why the company has grappled with the AI shift – lacking a coherent, crisp, and clear product strategy.

As Professor Christensen cautioned in his book, “If history is any guide, companies that keep disruptive technologies bottled up in their labs, working to improve them until they suit mainstream markets, will not be nearly as successful as firms that find markets that embrace the attributes of disruptive technologies as they initially stand.”

Google, as a company, has some of the best minds in the technology industry, especially in data, machine learning, and what is now colloquially known as artificial intelligence. It owns DeepMind, a leader in the field.

If you read its blogs and research papers, there’s no doubt about Google’s expertise, brains, and infrastructure to build a compelling next-generation search product that puts artificial intelligence at its core. It has ample data and intelligence to develop a search engine for a post-browser world where we “chat” with machines.

What’s missing is the willingness to break the status quo. When I think of Google, I can’t help but think of IBM and AT&T, two companies that had all the “brains” and “intelligence” to be big players in personal computing and the internet. Yet they allowed others to define the landscape of the future.

ChatGPT is foretelling a future where traditional input devices like keyboards and mice will be replaced by more interactive methods such as voice commands and gestures. In a mixed-reality world, navigating through information layers will rely on these intuitive interactions, diminishing the relevance of traditional web formats like 10 blue links and prompting the need for new monetization models.

For Google, as well as every media company reliant on advertising, the need to adapt is an existential question. Google today makes money by placing advertising links above and around search results. It can be difficult to distinguish between legitimate results and paid links. Nevertheless, paid links are directly correlated to what you searched for and occupy prime real estate. The real unpaid results are somewhere further down on the page. So, the more “ads” it can offer, the higher the odds of Google’s cash registers ringing. Google has been doing this very successfully — more lately, as it has tried to meet stock market expectations.

I did a rough back-of-the-envelope calculation. At the end of the second quarter of 2024, Google made $0.93 billion a day, or about 14.9 times as much as it did in Q2 2008 when it took home about $62 million a day in revenue. On June 30, 2008, Google stock was at $13.03. On July 1, 2024, it was $184 per share — roughly 14 times higher. As a company, it relies on people to keep searching so it can keep mingling paid (ads) results with organic results.

When the world transitions to a single query yielding a single answer, there will be fewer opportunities for “paid link” subterfuge. Even if Google shifts to serving ads based on semantics, they will have reduced opportunities to make money.

There is an argument to be made that traditional text-based search and browsers won’t die overnight, if at all. TV and radio networks are still around. But they don’t command a premium. TV networks are now primarily for selling boner pills and scaring old people into thinking they have some unpronounceable disease. Netflix saw a gradual decline in demand for DVDs, decided it was time to bet big on becoming a streaming-first company, and embraced the change to a broadband-first world. On the flip side, Blockbuster didn’t and turned into a flop.

What Google can’t afford: slowing (or lack of) growth. That will turn its stock into putty, which means it will fail to attract talent or develop a future. It will resort to financial engineering to appease Wall Street. And eventually, it will become a Yahoo.

It might not be today, tomorrow, or even 2025, but surely by 2030, we will see the impact of this new interaction behavior. Even Apple — a laggard when it comes to internet services — knows the change is coming. It is starting to give Siri an AI Botox and incorporate services like OpenAI. Apple is looking beyond the browser, and so is Meta.

Look at the urgency with which Mark Zuckerberg is trying to reinvent his company from within — starting with its attempts to incorporate generative AI into ad engines for its apps like WhatsApp and Instagram. Meta’s Llama push primarily is about advertising dollars. Use AI on Instagram, create AI bots, and at the same time help the company with the ability to put together insta-ads, no Mad Men required.

WHO’S WILL TAKE CHARGE?

Google needs to take decisive action, even if it means sacrificing some revenue to prepare for a new future. Its leaders must make tough calls, similar to Andy Grove or Steve Jobs — individuals who weren’t afraid to defend their vision to Wall Street while inspiring employees and maintaining conviction in their strategic direction.

The Google CEO’s job is made harder because the company lacks other product lines to bolster its revenue. Despite its best efforts, Google remains beholden to the search and search advertising model, making it vulnerable to sniper attacks from Microsoft and OpenAI.

Since OpenAI unleashed ChatGPT, Google’s response has been tepid, marked by the botched launch of its competitor, Bard, and modest AI integrations in tools like Google Mail. However, as (late) Clayton Christensen noted, “Disruptive technology should be framed as a marketing challenge, not a technological one.” The world hasn’t noticed.

Google needs to pull up its straps and get ready to fight to retain market share as it transitions to the new AI age. It doesn’t matter what technology they build and invents; unless it pushes to implement it, it will amount to nothing. Back in 2013, I publicly stated that Sundar Pichai was ready to be CEO — anywhere. He just happened to end up at Google.

On a flat wicket, Sundar has shown amazing skills to keep batting and batting. Now that the wicket has gotten sticky, and Google has been bowled a googly, what will he do?

Retired out is an honorable option!

Thanks to Fred Vogelstein, Hiten Shah, Matt Buchanan and Reeve Hamilton for their help with feedback, and suggesting some much-needed edits. No AI can replace your guidance and help. — Om

What is Yahoo’d?

Yahoo’d: a state of irrelevance.

Back in 1994, Jerry Yang and David Filo started Jerry’s Guide to the World Wide Web. It was a simple directory of websites organized in a hierarchical manner. The internet was small at that time, and in a way, it was easier to organize the information. (Fun fact: I sent Jerry an email to get my website included in the list.) The site was eventually renamed Yahoo, an acronym for “Yet Another Hierarchically Organized Oracle.” Its directory-like search was perfect for the slow-speed web of the mid-1990s. However, as the internet started to grow in size, Yahoo’s approach to organizing the internet began to show its weaknesses.

In the late 1990s, two other Stanford whiz kids, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, started Google — and it threw Yahoo for a loop. Page and Brin wanted to create a search engine that used a new way to show search results, based on what would eventually be known as PageRank. Their approach was driven by the idea that the number of pages on the internet would grow exponentially and that, with faster connections, people would look up information more often.

And they were right. With broadband proliferation, Google’s simple search page became the starting point for how we interacted with information. The faster the pipes, the faster and more often we went back to search for more things. Google was rewarded with all our attention.

At the start of 2000, Yahoo was still the preeminent place for most consumers to start their internet journey. It was the most valuable company on the planet — worth over $125 billion. It had passed on buying Google’s PageRank technology, which was on offer for a few million dollars.

It tried very hard to match Google by buying innovative companies such as Inktomi. It tried to jump on the Web 2.0 bandwagon. But in the end, it failed because it started to lose the “talent war.” Some of the smartest people worked for Yahoo, and then they worked at Google or some other high-flying startup. They would go on to do interesting and important things — just not at Yahoo.

Its ranks were filled with career managers who believed in the status quo, or at best incremental change, to ensure that Yahoo’s stock kept up appearances. Yahoo was on a road to irrelevance — a fate worse than being acquired by a telecom company. In 2017, the company was sold to Verizon for less than $5 billion — about the same as its annual revenue.

Google would go on to become one of a handful of American companies valued at more than $1 trillion. Yahoo, on the other hand, has become an afterthought on the internet, owned by a large private equity firm. These days, the only reason I visit Yahoo is to check the dismal performance of my fantasy baseball team.