For centuries, industries such as beer, wine and whiskey have been built on foundations of heritage and craftsmanship. Over time, these products have become precious, cultural artifacts, deeply tied to regional identity. The botti used for ageing Barolo wine in Piedmont, the ancient recipes used to produce beer in Germany, or the oak used for aging whiskey all carry symbolic meaning beyond their technical purpose. Entrepreneurs entering these fields quickly learn that innovation often means challenging industry traditions that entire regions have held sacred for generations. The price of novelty can be high: reputational risk, resistance from loyal consumers, even rejection from local communities who see innovation as an attack on authenticity. Inspired by research on the Swiss beer industry, this article proposes strategic ways of weaving centuries of tradition into new interpretations.

When Tradition Becomes a Barrier to Innovation

One of the most striking examples of tradition clashing with innovation comes from the Piedmont region in northern Italy. Barolo and Barbaresco wines, revered worldwide as the “king and queen” of Italian reds, have long been governed by very precise customs. The Nebbiolo grape must endure extended aging in large old oak barrels (botti), allowing the tannins to mellow slowly, resulting in a wine of power and structure meant for long-term cellaring. In the late 20th century, a group of modernist winemakers sought to adapt these wines to evolving tastes. They introduced shorter maceration times and used new French oak barriques, which produced wines with softer textures and earlier drinkability. While critics abroad praised these innovations, at home the backlash was fierce. Traditionalist producers accused the modernists of betraying the soul of the region! Local consumers boycotted the wine and restauranteurs refused to include it on the wine list. What outsiders saw as forward-thinking creativity, insiders saw as a type of cultural vandalism.

The beer industry provides similar cautionary tales. In Germany, the Reinheitsgebot, (a 16th-century “purity law”) still dictates that beer may only be brewed from water, hops, malt and yeast. While this law was originally intended to protect consumers and ensure consistency, it has become a cultural identity marker. Attempts by innovative brewers to incorporate ingredients like spices or unusual grains are often dismissed as “not real beer.” For entrepreneurs, this creates a paradox: consumers may crave novelty in other parts of their lives, but when it comes to their beer, many cling fiercely to the heritage they know and love.

Whiskey offers another perspective. In Scotland, the debate between single malts and blends has shaped the market for decades. Experimental distilleries that try finishing whiskies in unconventional casks, such as tequila or rum barrels, walk a fine line. While some enthusiasts welcome the creativity, traditionalists often dismiss such products as gimmicks that dilute the prestige of their legendary Scotch drink.

Blending Tradition with Innovation – Examples from Swiss Brewers

So, how do entrepreneurs manage to innovate and position novel products in industries marked by such traditions? Our research on the beer industry in Switzerland shows that innovation is certainly possible and, what’s more, can also become a thriving component of the brewer’s identity.

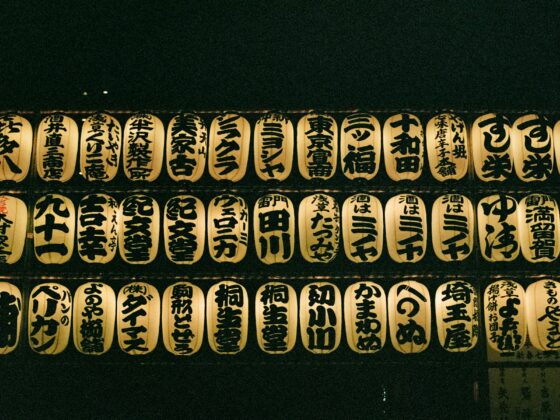

Brewing is one of the most ancient industries in Switzerland. Dating back to 450BC, the production of beer has been historically carried out in monasteries and by ancient breweries such as Feldschlösschen and Schützengarden. Traditional brewing styles vary across regions within the country with more pilsner and lager brews in the German side of the country. After the dissolution of the beer cartel during the 90s, entrepreneurs started to experiment with new recipes, ingredients, methods of production and business models. The result: a vibrant beer scene in the country with more than 1200 breweries across a country of nearly 10 million inhabitants, giving Switzerland the highest density of breweries per capita in the world. How has this been possible for entrepreneurs in the Swiss beer industry with production processes so heavily shaped by long-standing traditions and social norms?

Our research with brewers around the country reveals that an interplay between tradition and innovation is possible when the following factors are taken into account:

-

Authenticity matters

Relying on authenticity helps to create a sense of connection between modernist approaches and established traditions. For example, by referring to regional icons, historical sites or iconic characters, a cognitive bridge is created between an old brew and an innovative variation on the theme. Breweries such as Brasserie du Jorat, known for adding local herbs to their recipes, are aiming to highlight the local identity of the region. Their beer labels and mats also feature Swiss women wearing dirndls (traditional Alpine attire) and waving Swiss flags like true locals.

-

Tapping into heterogeneous markets

Tapping into multi-cultural markets can be advantageous when trying to challenge traditional recipes and production methods. The market’s cultural diversity means that expectations regarding traditions differ among international customers. This gives modernists the chance to experiment with ingredients, ageing methods, recipes and packaging without being pushed away by the market. For Swiss breweries, this implies launching their innovative products in multi-cultural cities and regions where more than one Swiss language is spoken and with a high number of commuters, expats, visitors, etc. Interestingly, Zurich, Geneva, Lausanne, Neuchâtel and Lugano host the highest number of experimental new breweries in the country.

-

Collaboration as bridges

Creating partnerships with traditional actors gives new brewers a boost in their status and acts as a signal of quality for consumers who are undecided whether to follow new approaches that challenge traditions. By creating such collaborations, beer entrepreneurs demonstrate their commitment to being an extension of past traditions, drawing inspiration from them rather than just being seen as disruptors. This is the case of young, entrepreneurial breweries joining the Swiss Beer Association (Schweizer Brauerei Verband, also known as SBV), such as the highly successful Doctor Gab’s, La Nebuleuse and Officina de la Birra.

Tradition and Innovation – Potential Partners

Making tradition and innovation co-exist implies much more than just simply recombining old and new. It requires a deep understanding of expectations, social norms and values embedded in industry traditions, combined with questioning how to challenge and evolve them respectfully. The Swiss beer industry demonstrates that innovation can thrive when entrepreneurs reinterpret the past through authentic cultural symbols. Collaborations with long-standing industry players provide credibility and trust, while multicultural markets create fertile ground for experimentation. Ultimately, the lesson extends far beyond beer, wine and whiskey: tradition and innovation are not opposing forces but potential partners. When approached with respect and imagination, innovation does not threaten heritage; in fact, it can be the key to safeguarding its relevance for generations to come.