You both also work in property and design. What bearing does that have on site selection and fit out?

Aushi Meewella: We were extremely picky about both the location and the building. It’s taken us over two years to find this site. We looked at a lot of opportunities in new build developments, but they didn’t fit with what we wanted to create. The building that houses Kolamba East (which is just off Liverpool Street in the Norton Folgate development) has a beautiful skeleton. There is a lot of exposed brick as well as antique features and high ceilings. We have infused a contemporary Sri Lankan aesthetic into what is a very east London property.

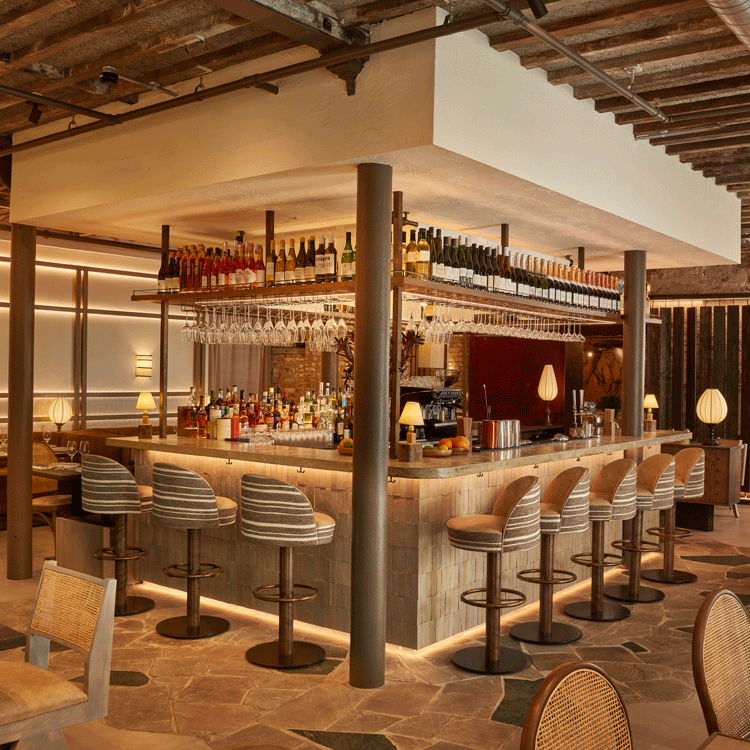

Eroshan Meewella: We’re opening a month later than we planned to. The site was delivered late by the landlord, and we also used a lot of Sri Lankan artisans for our furniture and art which made the supply chain difficult. But we’re delighted with the way the site looks. Working with Annie Harrison of London studio FARE INC, we have created a space that echoes the design of the Soho original and pays homage to the Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa, who pioneered the Tropical Modernism movement. The big difference Between Kolamba East and the original site is that this one feels a bit more refined and grown up as befits the location.

EM: We looked very closely at other key London restaurant hubs including Borough Market and Charlotte Street. We wanted an area that had a good catchment and other great independent restaurant brands. This part of east London ticks all the boxes as it’s where The City, Spitalfields and Shoreditch meet. There has been a lot of restaurant activity here recently.

AM: We’re a little hidden away in a courtyard and are among the first operators to launch here but there will eventually be five or six premium independent restaurants here.

The site is much bigger than your original Soho venue. How has that changed things?

AM: The menu will be more expansive because we have more seats (around 90) and a bigger kitchen. But for us the biggest benefit of having a larger space on one storey (Kolamba Soho is spread over two) is that we can have a proper bar, which provides a focal point for the space

EM: It will change our business model for the better. Typically, restaurants are 70:30 for food and drink but at Soho our drinks spend is lower because we turn our tables quickly. Kolamba East will hopefully have a better balance between food and drink sales.

Is it true that the two restaurants won’t have any dishes in common?

EM: There will be a tiny bit of overlap, but everything has been tweaked for the new menu. Kolamba East’s menu is a little more upmarket but we’re not doing fine dining. Our most expensive single dish is £34 and that is designed for two or more people to share.

Your dishes are based on family recipes. How do you make these suitable for a London restaurant?

EM: We both grew up in Sri Lanka, so we know how the food is supposed to taste. We then ask our chefs to scale the recipes up and work on the presentation. Indian restaurant operators have been very successful in taking dishes that have their roots in people’s homes and presenting them in a more contemporary way.

AM: We tweak dishes without losing the essence of them. For example, a new dish for Kolamba East is hot butter soft shell crab. In Sri Lanka, it’s typically made with cuttlefish.

How important is it to have Sri Lankan chefs in the kitchen?

EM: Our executive chef is Indian. But the core cooking team is made up of five or six senior Sri Lankan chefs. Imran (Mansuri) has worked at Michelin-starred Indian restaurants including Tamarind and Jamavar and has joined the team to set standards and bring some refinement to the dishes. I work closely with the kitchen team and am involved in recipe development because we don’t want to lose the Sri Lankan-ness of the dishes. Everything you taste at Kolamba should take you back to the island.

AM: One of the downsides of having lots of Sri Lankan chefs is that they tend to have a very high tolerance to chilli. Because of this, having other nationalities in the kitchen is a good thing.

In the UK, Indian cuisine is often perceived as not being suitable for lunch. Does this spill over into Sri Lankan food?

EM: Yes. But our food is closer to Thai in lightness. If you come and have our chicken curry with dahl and rice for lunch you won’t leave feeling heavy.

AM: We also offer string hoppers (rice floor noodles) which are even lighter and we’re big on vegetables dishes, too. Most Indian food in the UK is big on ghee, butter and cream. Their curries tend to be heavier. The flipside to that is that some diners equate richer things with value for money.

What are the main misconceptions around Sri Lankan food?

AM: The big one is that people think it’s the same as Indian food. It’s understandable because Indian food has dominated the south Asian market in the UK for over 50 years. But there are important differences. We cook with coconut milk, so our dishes are often naturally vegan, and we use more chillies. In general, the further you travel down the Subcontinent the spicier things get.

EM: Sri Lankan food has only been visible in central London since Karan (Gokani) launched Hoppers in 2015. The segment isn’t even 10 years old yet. There are now several other modern, high-quality operators in the space including ourselves, Paradise and Rambutan but Sri Lankan food is still miles behind Indian food in terms of people’s understanding. For most people, Sri Lankan cuisine remains unfamiliar. For that reason, it can be a tough space in which to operate.

Can we expect to see a Kolamba South or North anytime soon?

EM: When we started out in restaurants a lot of people told me that a single site would be a lot of work for very little return. We have absolutely found this to be the case, especially when a comparison is made between our original restaurant in Soho and our property and design business (WhiteBox London).

AM: We want to grow but we don’t want to become a chain. Our restaurants will continue to have their own identity and be independent in terms of menu development.

When you launched the original Kolamba in 2019 you said you felt like outsiders. Is that still the case?

EM: We’ve learnt a lot over the past five years, but it’s been chaotic with Covid, cost of living and challenges around labour, energy and the cost of our ingredients. We’ve done a reasonable job of establishing Kolamba Soho on the London restaurant scene, but equally I would not say we’re that well-connected with our peers. With another business to run, our biggest challenge is bandwidth.