The Future Is No Longer What It Used To Be

To write about the future is, inevitably, to be wrong about the future. I have repeated this for years, and yet, it remains the truest sentence I know. The mistake, however, is not a failure of prediction but a form of knowledge. We now inhabit a “post-postmodern”, almost “post-futurist” condition, a time in which tomorrow no longer stretches ahead as a horizon but hovers above us like a permanent update, endlessly refreshing itself. And although the Singularity that Kurzweil foresaw two decades ago has not yet fully arrived, his law of accelerating returns already permeates the present, altering our perception of time and possibility. Within this landscape, those of us who attempt to understand technology are no longer prophets, but rather cartographers of the impermanent, tracing transient patterns across the shifting topography of innovation. What follows, therefore, are not laws but coordinates, ten mutable constellations, ten subtle tremors that delineate the tectonic rewriting of business, technology, and meaning itself. Because the future, in the end, is no longer what it used to be.

Enjoy the ride.

To write about the future is, inevitably, to be wrong about the future

1. Zero Click And The Dissolution of the Blue Link Hegemony

The web as we knew it is quietly dissolving into something else. For three decades, we followed links, counted clicks, and navigated the blue constellations of search results as if they were landmarks on a digital map. That world, however, is fading. We no longer search in the classical sense; we ask, and we are answered, instantly, synthetically, and without having to move around different websites.

The introduction of Google’s AI Overview and AI Mode, along with the spread of answer engines such as ChatGPT, Perplexity, Claude, etc., signals the decline of the aggregative web and the birth of a new, generative one, a post-search Internet. In this new regime, information behaves less like geography and more like theology. What we’re looking for is no longer found in places we journey to, but revealed through “invoc-AI-tion,” through the exoteric (rather than esoteric) ritual of the natural language.

From a business standpoint, the numbers are unambiguous. A recent Search Engine Land study reported that when AI Overviews appear in Google search results, traditional click-through rates to websites drop by 30–35 percent for informational queries. The same study found that zero-click searches (those in which users find what they need without visiting any site) grew in the U.S. from 24.4 percent to 27.2 percent within a year, while the organic click-through rate fell from 44.2 percent to 40.3 percent. Simultaneously, Similarweb reported that referral traffic from Google declined by nearly 10 percent year-over-year, even as total searches increased, meaning that more queries are being resolved inside the generative layer itself.

For businesses, this also means that audiences are becoming invisible to traditional metrics. Demand still exists, maybe even more so, but it now flows beneath the surface of measurable behavior. You cannot track on Google Analytics a click that never occurred, nor can you quantify an interaction that takes place entirely within an AI-generated summary.

You cannot track on Google Analytics a click that never occurred.

Visibility persists, yet it has migrated to a dimension that our current instruments cannot (and perhaps will never) be able to track. This transformation calls for more than tactical adaptation. It demands a redefinition of what brand presence means, and of the very metrics (or the lack thereof) by which we attempt to measure it.

2. AI Ads: The End of the Click Economy

The pay-per-click model was born in the twentieth century, and it will likely die with it. What began as a transactional exchange (attention traded for currency) has likely reached its evolutionary endpoint. We are entering the age of pay-per-mention, where advertising dissolves into the very syntax of generative systems, woven invisibly into the linguistic fabric of AI. In this new order of (anti-)search, the algorithm does not display advertising; it IS advertising.

In this new order of (anti-)search, the algorithm does not display advertising; it IS advertising.

In an AI-centered search engine paradigm, visibility and monetization have merged into a single generative layer. Google’s AI Overviews, launched globally in 2024, exemplify this shift. These summaries, which appear at the top of search results, now include advertising dynamically inserted above, below, or directly within the AI-generated response, marked with a small “sponsored” label. The ads are contextually matched to the intent behind the query, not just to its literal keywords (i.e, a user who asks how to remove a wine stain might be shown an ad for a cleaning product without ever having expressed commercial intent), and the position and content of each ad are generated in real time, based on the AI’s interpretation of the search journey and contextual signals derived from Google’s vast auction ecosystem.

Early data show the magnitude of this transformation. According to Wordstream and HubSpot, average click-through rates across Google Ads have dropped by over 20 percent since 2022, while investment in generative and conversational ad formats has grown by more than 70 percent year over year. As reported by Oppenheimer, Alphabet’s ad income increased by 11 percent year over year, largely fueled by the integration of AI-driven placements and the growing volume of searches triggered by conversational interaction.

This reconfiguration has deep implications for advertisers. First of all, participation is not optional: eligible campaigns are automatically included in AI Overview placements. Second, at least for now, reporting granularity remains limited. Google Ads does not yet provide segmented performance metrics specifically for AI Overview placements, making ROI analysis challenging. Nevertheless, the trend is unmistakable: search is becoming conversational, and advertising is dissolving into the flow of discourse itself.

The CTR, once the heartbeat of digital marketing, is becoming an anachronism, the faint echo of a dying interface.

The CTR, once the heartbeat of digital marketing, is becoming an anachronism.

The future of advertising will not be measured in impressions or clicks, but in mentions, contexts, and correlations. And, as language becomes the medium of commerce, marketing itself becomes a form of semiotics.

3. Agentic AI: From Search Engines to Do Engines

The rise of agentic models signals a gradual passage from ask-and-answer to say-and-act. These systems can write, book, plan, execute, and decide, moving beyond assistance into orchestration. According to McKinsey, over 38 percent of enterprises have already deployed autonomous or semi-autonomous AI agents for internal workflows, customer service, and marketing operations, up from less than 10 percent just two years ago. OpenAI’s latest data confirms that more than 1.2 million GPTs have been created since late 2024, many functioning as self-directed agents capable of retrieving information, triggering tools, and executing real-world actions.

But the change extends far beyond corporate infrastructure. It is reshaping the daily behavior of users. Consumers still open browsers, compare options, and scroll through results but increasingly, they delegate. Instead of searching for a restaurant, they might say, “Book me a table for two at a good Italian place nearby,” and the system completes the process without ever displaying a single link. The user’s intent flows directly into execution, and the interface begins to dissolve into the background of life.

This is not a clean replacement of one paradigm by another, of course, but a gradual overlap.

For companies, this duality changes where and how visibility occurs: the more we trust machines to act, the more invisible our interactions will become, and, in that invisibility, a new economy of agency is quietly taking shape.

Two recent developments illustrate the magnitude of this shift. Last week, OpenAI transformed ChatGPT into a “travel mall”, integrating built-in apps from Expedia Group, Booking.com, Uber, and Tripadvisor. Users (and, of course, agents) can now search, compare, and book directly inside the chat, bypassing the open web entirely. The experience is fast, frictionless, and centralized. The second event, ChatGPT’s launch of “Instant Checkout”, deepens this logic. Built on the Agentic Commerce Protocol and powered by Stripe, it allows humans and agents to purchase from Etsy and Shopify merchants directly within the chat. This move transforms conversational AI from a tool of information retrieval into a transactional infrastructure.

If search engines sought to index the web, do engines seek to enact it, and the future of marketing will not lie solely in optimizing for human attention, but in designing for algorithmic trust.

If search engines sought to index the web, do engines seek to enact it.

4. Vibe Coding: The Poetics of Code

Vibe coding is the art of writing software code through natural language. Iconic music producer Rick Rubin recently captured the spirit of this shift in his book The Way of Code: The Timeless Art of Vibe Coding.

True to his philosophy, Rubin treats code not as machinery but as vibration, a matter of tone, texture, and presence. However, even though I am a Rubin megafan, I must admit that stories of human debugging in vibe-coded systems are still plentiful. Models sometimes misread nuance, get the mood right but the logic wrong, and fail where precision hides behind metaphor. Yet, like all emerging languages, vibe coding will find its balance.

The data already show momentum. According to GitHub, AI-assisted coding now accounts for 46 percent of new code on the platform, and over 60 percent of developers under 30 use natural language or conversational tools in their workflow. Gartner predicts that by 2027, prompt-based development will be used in more than 70 percent of UX and front-end design projects (and that, IMHO, is where vibe coding truly shines, as it is perfectly suited to the front layer of experience: user interfaces, brand environments, interaction design, etc.).

In this light, we are already witnessing startups producing MVPs almost entirely through vibe coding within just a few weeks. Even if such prototypes still require significant human debugging, this is merely a transitional phase. The trajectory is clear. We are moving toward a paradigm in which fluency in natural language, and especially in English, will hold greater value than proficiency in traditional programming syntaxes such as Python or JavaScript. The grammar of the future will not be written in C++ but in English, and to know how to CODE for a machine will soon matter less than knowing how to TALK to a machine.

The grammar of the future will not be written in C++ but in English, and to know how to CODE for a machine will soon matter less than knowing how to TALK to a machine.

5. The Post-Browser-Web: When the Interface Disappears

The browser, once our portal to the WWW, is becoming an archaeological artifact. Interactions now flow more and more through messaging layers, voice systems, and invisible infrastructures. We are moving into a world without browsers, as the interface dissolves into language itself. You can now, for example, chat directly with ChatGPT through WhatsApp at +1 800 242 8478, transforming what was once a screen-mediated act into something almost oral, intimate, and frictionless. The machine is no longer on the other side of the glass but within the same communicative fabric as our friends, families, and colleagues.

This evolution is not theoretical; it is already measurable. According to Similarweb, global web traffic to traditional search engines has fallen by more than 12 percent year over year, while the use of AI-driven conversational platforms has surged. Perplexity, which recently introduced a WhatsApp integration for global users, reports that its active user base grew by over 80 percent in Q3 2025 alone, with more than 70 percent of queries now arriving via mobile and messaging channels rather than browsers. In parallel, OpenAI confirmed that over 100 million users now access ChatGPT through mobile or integrated chat experiences, bypassing the browser entirely.

The change will not happen overnight, yet it is already unfolding in subtle, domestic gestures. When my mother, in her seventies, opens WhatsApp to ask ChatGPT for a recipe, it becomes clear that this is no longer a generational revolution but an intergenerational one. Remember the browser wars of the 1990s? In the end, everyone lost.

Remember the browser wars of the 1990s? In the end, everyone lost.

6. Conversational Reporting: The Oracle of Data

Wherever there has been business, there have always been data, and in hospitality, the same law applies. From the earliest paper ledgers to Excel spreadsheets, and from dashboards in Tableau or Power BI to modern BI ecosystems, every era has tried to make sense of the invisible patterns that govern performance. Now, we stand at the threshold of a new stage: conversational, predictive, even prescriptive reporting.

This transformation is especially fascinating in our industry, where predictive and conversational analytics could quickly become the new lingua franca of management. With a simple LLM integration, a hotel manager can now ask, “What was the average time to clean a room last week?” or “How many maintenance issues recurred in the spa area?” and receive an instant, contextual, and even prescriptive response.

With a simple LLM integration, a hotel manager can now ask, ‘What was the average time to clean a room last week?’ and receive an instant, contextual, and even prescriptive response.

I recently worked on a project in predictive maintenance that perfectly illustrates this shift. We trained a machine learning model, integrated with an LLM, to analyze all the guest incidents that had occurred in a hotel over the previous ten years in order to forecast where the next ones were most likely to happen. The system achieved remarkable accuracy. Seeing a model anticipate operational issues before they emerged was not just technically impressive; it was philosophically provocative. The hotel, once reactive, became precognitive.

The implications are profound. The “Human-in-the-Loop” model, where automation and human intuition coexist in a single operational flow, ensures that technology amplifies human intelligence rather than replaces it. In this sense, AI-powered conversational reporting becomes a modern oracle: precise, tireless, and seemingly omniscient. Yet this proximity to omniscience carries its own peril. When data begins to speak, humans risk ceasing to think, and when interpretation fades, hallucination takes its place.

Want an example? I have written extensively about this phenomenon in From “Gig” to “Glitch” Economy: Hospitality’s New Battle Against AI Hallucinations, yet it continues to baffle me. Recently, Google’s AI Overview confidently declared that Peter Hook, the legendary bassist of Joy Division and New Order (and a personal hero of mine), is the founder of my consulting firm, Travel Singularity. As much as I would have loved to call him my boss, this is, of course, entirely untrue (and the only connection between us is that my company once co-sponsored one of his concerts a few years ago).

Moments like these reveal the paradox of generative intelligence: the oracle speaks, but not always truth. And yet, even through its hallucinations, it learns. These systems will evolve, as all languages do, by misfiring their way toward meaning.

7. Apps Inside AI: The Dissolution of Software

With the integration of external apps described in Point 3, ChatGPT is becoming the new post-browser of reality. Platforms such as Spotify, Canva, The Fork, and Shopify are now accessible without ever leaving the conversational frame. The AI becomes the universal interface, not one among many, but the only one: AI as the only possible UI.

The AI becomes the universal interface, not one among many, but the only one: AI as the only possible UI.

What is happening to apps mirrors what has already begun to happen to the web: the visible layer is collapsing inward, absorbed into the flow of dialogue. The browser is dissolving into the AI, and applications are following the same path. This is the death of the app as an object and the birth of the app as an enabler, a function without a face, a process without a portal.

I can now ask ChatGPT to “create a playlist of Atmospheric Black Metal” directly within the conversation, without ever opening Spotify. The same applies to designing in Canva, booking a table through The Fork, or purchasing an item on Shopify. The command line has become a sentence; the interface, a conversation.

Mark my words: there will be no more icons on our iPhone screens, no folders to navigate, no windows to open or close. Only language. The interface, once a surface we touched, becomes an atmosphere we inhabit: invisible, omnipresent, and continuous.

Mark my words: there will be no more icons on our iPhone screens, no folders to navigate, no windows to open or close. Only language.

The future of software is not interaction but disappearance. We will not use programs. We will simply summon them.

8. Conversational Commerce: The Return of the Voice

e-Commerce is transforming into AI-commerce. I have already written about this shift in Point 3, when discussing Instant Checkout, where users can now complete purchases directly within the chat interface.

This is not merely a new feature; it is a paradigm shift. The act of buying, once mediated by screens, pages, and clicks, is being reabsorbed into language itself. In this trajectory, the entire web of the future could become a one-stop shop, where the “shop” is not a website or an app but the conversational platform or even the wrapper of one.

The entire web of the future could become a one-stop shop, where the “shop” is not a website or an app but the conversational platform.

Whether it is ChatGPT, Perplexity, WhatsApp, or the latest “AI tech vendor” layering its interface over a pre-existing model, the surface through which we speak becomes the marketplace in which we act.

Commerce is dissolving into conversation, and conversation into infrastructure. And, soon, the main question will no longer be where to buy, but how to speak in order to buy, and the next battle of capitalism might not be for attention but for articulation…

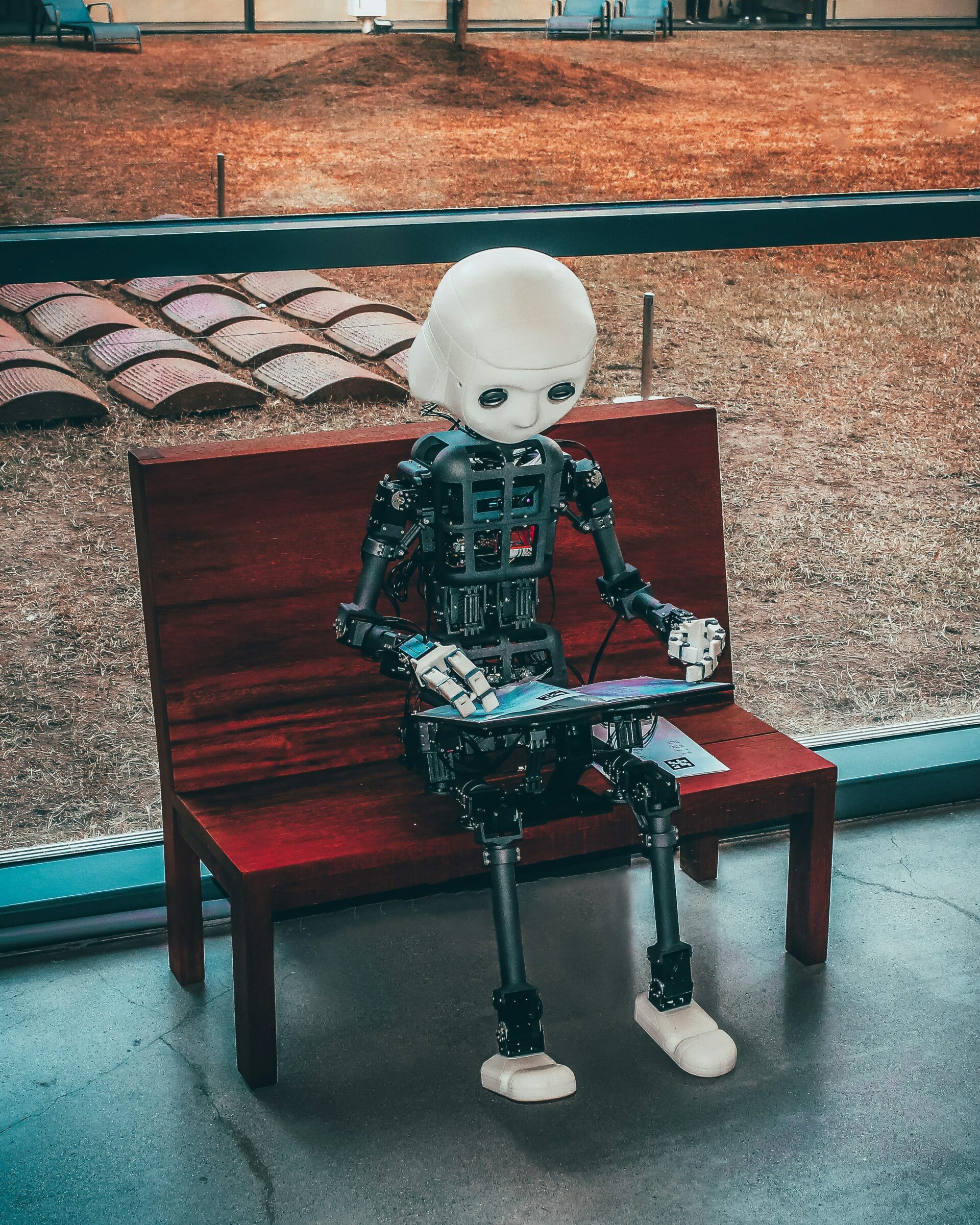

9. Digital Workers: The New Class of the Hybrid Economy

The conversation around digital workers is a particularly delicate one. On the one hand, collaborative automation genuinely improves human working conditions by liberating humans from repetitive, mechanical tasks. On the other hand, we cannot ignore the growing temptation to replace humans altogether.

In my experience over the past year and a half, the majority of consulting requests I have received (and almost all of which I have declined) were not about “how to improve existing workflows” but rather “how to eliminate 30 percent of the human workforce”. We now stand between the promise of liberation and the threat of redundancy.

We now stand between the promise of liberation and the threat of redundancy.

Digital workers are non-biological agents integrated into human workflows, performing real and measurable productive functions. The purpose of automation, in its most ethical form, is not to erase human work but to elevate it, yet the data reveal a more complex reality. According to internal figures reported by Business Insider and The Information, one out of every three “workers” at Amazon is now non-biological, a robotic or digital system integrated into its logistics and fulfillment network. Amazon’s robotic workforce surpassed 750,000 autonomous units in 2025, processing over 70 percent of orders without direct human intervention, and the company’s humanoid warehouse robots cost around three dollars per hour to operate, compared to more than thirteen dollars for their human counterparts.

The logic is clear: as the cost of human labor continues to rise (up over 200 percent since 1990) the cost of robotic labor has dropped by more than 50 percent over the same period (Zippia, 2024). The economic incentive is enormous, and the trend toward human replacement undeniable. The phenomenon is not new. During its peak, Kodak employed around 145,000 people; when Meta acquired Instagram for twelve billion dollars, the company had just twelve employees. A ratio of 1 to 12,000 that reveals the accelerating asymmetry between capital and labor. As humanoid labor becomes cheaper and algorithmic cognition more efficient, we may be approaching not a crisis of unemployment, but of unemployability. If productivity decouples entirely from human labor, we will have to rethink the very structure of the social contract.

As humanoid labor becomes cheaper and algorithmic cognition more efficient, we may be approaching not a crisis of unemployment, but of unemployability.

A universal basic income is often presented as the inevitable conclusion of the automation age, a fair and elegant solution to the displacement it creates. It sounds persuasive in theory, but perhaps too clean to be real. The logic seems straightforward: as automation lowers production costs, purchasing power should expand even without traditional employment. In Moore’s Law for Everything, Sam Altman predicts that within a decade, AI could generate enough wealth to provide every adult in the United States with $13,500 per year, a redistribution made possible by the radical deflation of goods and services.

Yet to believe this techno-utopian vision blindly is to indulge in a form of techno-naïveté. It assumes that efficiency translates naturally into equity, and that the same system that created economic inequality will somehow dissolve it through generosity. In reality, wealth may concentrate faster than it circulates, and the dividends of automation may not reach the displaced.

To believe this techno-utopian vision blindly is to indulge in a form of techno-naïveté. It assumes that efficiency translates naturally into equity, and that the same system that created economic inequality will somehow dissolve it through generosity.

The philosopher Mustafa Suleyman, co-founder of DeepMind, was more candid at the 2024 World Economic Forum: In the long term, these [AI software] are fundamentally labor-replacing tools.

His statement strips away the comfort of utopia and forces us to confront the possibility that the end of work may not come with a safety net.

In a recent conversation with my friend Mark Fancourt, our discussion moved in precisely this direction. Our shared vision of the future of labor in hospitality (and, by extension, of hospitality itself) appeared less utopian and more unsettling. The promise of a perfectly balanced hybrid economy, where humans and digital workers coexist harmoniously, began to look more like a fragile negotiation between relevance and redundancy. As Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams urge in Inventing the Future, we can still demand full automation, demand universal basic income, demand the future

. But perhaps the truly radical act today is to question whether such a future would still have a place for us, or whether, in demanding it, we are only accelerating our own obsolescence.

10. Humans-as-Luxury: The Rarity of the Human

At the opposite end of the spectrum, to escape the dystopian horizon of total automation, a different trend is quietly emerging, one that restores value to the human.

In an age where digital workers multiply and biological presence becomes scarce, humanity itself turns into a form of luxury. As I argued in Humans-as-Luxury, human labor will not vanish; it will become premium. The hotels of the future will not be ranked by stars, but by the number of biological staff they employ.

Human labor will not vanish; it will become premium. The hotels of the future will not be ranked by stars, but by the number of biological staff they employ.

To be served by a person, to hear a trembling voice, to receive a handwritten note, these gestures will acquire the aura once reserved for silk or gold.

This idea is not speculative. Data already show the growing rarity of human work in hospitality. Despite an estimated 700,000 hotels worldwide, the entire global hospitality workforce numbers only 270 million people, barely 3.3 percent of the world’s population. Since the pandemic, this number has been in steady decline: one in two graduates from elite hotel schools like EHL now pursue careers outside the sector, choosing finance, consulting, or luxury brand management instead. In the United States, hotel wages have risen by 29 percent between 2019 and 2023, yet recruitment and retention remain critical challenges, with annual turnover rates hovering between 31 and 34 percent. In short, the human touch in our industry is disappearing, not because it lacks value, but because it has become economically unsustainable.

The human touch in our industry is disappearing, not because it lacks value, but because it has become economically unsustainable.

As scarcity deepens, its symbolic power grows. What is rare becomes precious. We are already seeing early signs of this: high-end properties now emphasize “authentic human contact” as a differentiator, promoting interaction with “real people” as part of the guest experience.

Yet there is also a deeper aesthetic and philosophical dimension. As Italian philosopher Mario Perniola suggested, the shift from the organic to the inorganic is not merely technological but cultural, and it changes our sense of beauty, presence, and being. Hospitality, by contrast, may become the last bastion of what is authentically human. In a future dominated by synthetic cognition, being welcomed by another person could feel as extraordinary as owning an original artwork in a world of reproductions.

In this sense, the “Humans-as-Luxury” paradigm offers not a naïve escape from automation, but a rebalancing of value. If the fully automated economy threatens to make us redundant, this countercurrent reminds us that scarcity creates worth, and that the presence of a human being (fragile, slow, and imperfect) might soon be the rarest and most coveted experience of all.

If the fully automated economy threatens to make us redundant, this countercurrent reminds us that scarcity creates worth, and that the presence of a human being might soon be the rarest and most coveted experience of all.

Epilogue

As I said at the beginning, to write about the future is, inevitably, to be wrong about the future. But someone has to write about it. Every generation invents its own form of prophecy, and ours happens to be written in code.

Many of these predictions will prove mistaken, yet one truth remains: the future will not (unfortunately) arrive in the form of flying cars, hoverboards, or sentient machines rising from factory floors. It will come quietly, through syntax and software, through the invisible grammar of our tools. And like all transformations that begin in language, it will unfold first in how we think, then in what we believe, and finally in what we are.

For business, this means the real frontier is no longer technological, but cognitive. The companies that will thrive in the coming decade will not be those that simply adopt AI, but those that learn to align human intuition with synthetic reasoning, to orchestrate ecosystems of cognition rather than hierarchies of command.

The next CEO will be less a manager of processes than a curator of signals, someone capable of conversing fluently across human and non-human minds. Strategy itself will become conversational, recursive, and alive.

If there is a moral to this “new normal”, it is this: the web was our mirror, and AI will be our echo. In that echo, if we listen carefully enough, we may still hear the faint, trembling frequency of the human, hesitant, imperfect, unoptimized, and therefore alive.

And if not, well, as the Monty Python crew wisely reminded us while whistling their way through the apocalypse…

Always look on the bright side of life.